Content

1877 to 1890: The patent office comes into being

On 1 July 1877, a Sunday, the Imperial Patent Office was established in the course of the entry into force of the new Patent Act. Formerly, the applicants had to comply with the acts and requirements for patents applicable in Prussia, Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony or other regions - depending on which of the 25 small states of imperial Germany they lived in. The establishment of a central German patent office, for the first time, provided uniform protection for inventions in the German empire - no matter whether they came from Bückeburg (Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe), Neustrelitz (Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz) or Greiz (Principality of the Reuss Elder Line). The patents were based on uniform principles and had unitary effect for the whole of the territory of the German empire.

While none of the formerly applicable patent acts had provided for the publication of the patents, the new uniform Imperial Patent Act stipulated that the essential content of the applications should be published in the imperial law gazette and the complete applications should be laid open to public inspection. Following the British model, patent specifications were printed after grant.

Imperial Patent Office in Berlin,

first office building on Wilhelmstraße 75

© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290 Nr. II9450

The first Imperial Patent Act was a substantial step forward for the patent system and, for the first time, it offered those who had successfully applied for a patent for an invention secure industrial exploitation of their invention beyond the borders of their home state. This development in the field of industrial property protection occurred for good reason; it was the time of advanced industrialisation in Germany and in many countries in Europe.

From 1877 to 1881, the first President of the new office was Dr Karl Rudolf Jacobi, "von Jacobi" after he was ennobled on occasion of his retirement. Jacobi was a lawyer and ministry official with more than twenty years of experience in the Prussian administration.

Furthermore, the Imperial Patent Office had 21 legally qualified and technically qualified members as well as 18 other staff (civil servants, employees and labourers), including three "registry attendants".

Karl Jacobi, the first President of the Imperial Patent Office

The work at the patent office was not the main occupation of the members: to ensure that they continued to gain practical experience in their technical field and were familiar with the respective search file, they had an appropriate main occupation, for example, working as chemists. They were appointed in an honorary capacity either as permanent members of the patent office (for life or for the duration of their main occupational activity) or as non-permanent members (for five years).

Cooperation between technically and legally qualified members

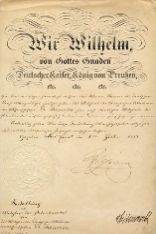

Certificate of appointment of Werner Siemens, since 1888 "von Siemens"

© Siemens Corporate Achives

The publication commemorating the 50th anniversary of the patent office, in 1927, states that in the initial 14 years - that means from the establishment of the office in 1877 to the entry into force of the new (second) version of the Patent Act of 7 April 1891 - the structure of the office had been of "a more preliminary nature. The work at the patent office was only a subsidiary occupation for all members. The legally qualified members were senior civil servants of other authorities, the technically qualified members were experts who had a recognised reputation; some of them were senior technical civil servants of other imperial or state authorities, some of them worked in industry."

Due to its responsibility at that time as a judicial institution, the office had technically qualified as well as legally qualified members (as mentioned above). In the commemorative publication, mentioned above, cooperation between the members is described as follows: "Mutually influencing each other, the lawyer has to acquire an understanding of technical subjects, the technical expert of legal issues, the former has to learn to think in concrete terms and the latter to think in conceptual terms. To achieve this goal it is necessary to fill the individual posts at the patent office with appropriate, suitable technical and legal experts [...] which requires a careful selection of civil servants who have to have an understanding for as well as a disposition and an inclination to such cooperation. However, in the light of the experience gained, it can be stated with satisfaction that technical and legal experts have generally worked together in a smooth and satisfactory manner."

One of the "carefully selected" staff members who worked at the Imperial Patent Office right from the start and essentially contributed to the success of the newly established authority was the entrepreneur, inventor and politician, Dr Werner von Siemens. As chairman of the then "patent protection Society" he strongly lobbied for the creation of a uniform German patent act and for the establishment of a central authority for industrial property protection in the German empire.

The staffing level of 40 imperial officials was soon exceeded: the large increase in all fields of business, particularly in patent applications, soon led to complaints because the staff was overburdened and even overworked. To solve this problem, additional civil servants were added to the workforce, which in turn resulted in larger space requirements of the office.

The office grows and expands

The first move took place in 1879, only two years after the foundation of the Imperial Patent Office: from Wilhelmstraße 75 (by the way, located directly next to the then office building of the Foreign Office) the Patent Office moved to Königgrätzer Straße 10, today's Ebertstraße. In the following years, further rooms in diverse Berlin buildings were added so that another move to a building sufficiently big to again house all divisions of the patent office under one roof became an absolute necessity: as from 1882, the new address was the building on Königgrätzer Straße 104-105. Today, this section of the street, located further south, is called Stresemannstraße. However, as early as 1891, the more than 230 staff had to move yet again - and, of course, that move was not to be their last.

The increased space requirements were caused by the changed personnel situation as well as by the constantly growing number of books, journals and other print products, which were kept in the office's own library, in particular, for the examination of novelty of an invention. Right from the beginning, the holdings of the library had also included rare historical works and official publications of foreign patent offices; only two years later, in 1879, the library held as many as 12,900 titles in total. In addition to buying new national and foreign publications, patent documents from abroad were also acquired by exchange: only few years after its foundation the Patent Office ran regular exchange schemes with 15 countries. Another important "source of supply" for the library were donations bestowed on the patent office by institutions and chambers of trade (programmes and annual reports), companies (sales brochures), foreign governments (patent publications) or private individuals. R. Fiedler, an engineering expert working at the Imperial Patent Office, described the compilation of his own search basis in his book "One hour at the Imperial Patent Office", which was published in 1905 by the publishing house, Mesch & Lichtenfeld, in Berlin. According to this book, the figures in American patent specifications, published in the weekly Official Gazette, were carefully cut out, classified and stuck into what was referred to as "American Atlas", which - with many thousand sticky notes - formed, as Fiedler wrote, a "fatal search material for many a patent application".

Statistical developments in the patent area between 1877 and 1926

After the move of the Imperial Patent Office in 1882, the library rooms for the first time also included a public reading room for interested users. In this room, anybody had the opportunity to search for the "latest state of the art", which was documented for all technical fields at the Patent Office and played a crucial role in the examination of patent applications.

There was an extremely great demand among inventors for the new uniform patent: while in the founding (half-)year of 1877 3,212 patent applications had been filed and 190 patents had been granted, these numbers rose steeply in the subsequent years. In 1890, 4,680 patents were granted - in respect of 11,882 patent applications.

Patent specification No. 1

The patent specification No. 1 with the filing date of 2 July 1877 was issued for the invention "Process for manufacturing a red ultramarine colour" by Johann Zeltner from Nuremberg.

In the founding year, the Imperial Patent Office also granted the patent No. 1250 for the "refrigeration machine", invented by Karl Linde from Munich. These and further pioneering innovations from 1877 until today are available in our poster gallery (in German) on the Internet.

Pictures: DPMA (unless otherwise noted)

Last updated: 10 December 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media