Content

Sophisticated architecture: the Imperial Patent Office from 1901 to 1910

Negative effects! This is what many - even famous people like Otto von Bismarck feared would happen - when the Imperial Patent Office was established in 1877. They thought that it would pose a risk to the "natural gainful occupation" of imitators or to industrial progress. However, this fear ebbed away and, in 1902, the then State Secretary of the Interior, Graf von Posadowsky-Wehner, acknowledged that the office was a well-established institution: "In most fields, industrial progress and patent protection are so intimately connected that our industrial life has become unthinkable without patent protection."

Did the office plan with foresight?

This was not the case, at least when the first new building on Luisenstraße in Berlin was constructed in 1891. Shortly after the completion of the building, when the office had only just moved in, it was for certain that the building was too small. President Otto von Huber (1895-1902) was determined to avoid, in the future, the unfortunate circumstance of spending many years having to relocate. In his very last year at the office, he approved the construction plans for an impressive building.

Präsident Otto von Huber (1895-1902)

The necessary building area alone measured a grand 23,600 square metres, bigger than two football pitches. It was not easy to find such a large area, even more so as the property had to be located centrally. The site of disused military barracks (Garde-Kürassier-Kaserne) seemed to be suitable, but the plot was too small by several hundred square metres, which were part of private properties. The price for which the owners agreed to sell their land to the empire, whatever amount it was, regrettably, has not been handed down. The area - just like today - stretches the entire length of Gitschiner Straße, from Alte Jakobstraße to Alexandrinenstraße.

Aerial view of the office (Source: Bavaria Luftbild Verlags GmbH)

The main entrance at the corner of Alte Jakobstraße and Gitschiner Straße was adorned with two corner towers, looked impressive and promised something big. Visitors crossing the threshold into the entrance hall probably stopped awestruck and stood still. What they inevitably first saw when they entered the building was a stone stairway taking up the entire width of the entrance hall and leading to the level of the ground floor. At the same time, they got the impression of looking into a cathedral with ribbed vaults. In the upper part of the stairway, several columns rose up to the ceiling, whose capitals supported the vault. There, at the top of the stairs, the doorman stood wearing a smart uniform with a matching hat, doubtlessly showing an imperial Prussian solicitousness.

Imperial Patent Office: main entrance

The complex had more than 700 offices for just under 1,000 staff - four times more than formerly - twelve conference rooms, eleven cash offices, three rooms for the legal office and one big search room. The library was housed in its own section of the building stretching over six floors. The individual floors were accessible via stone staircases with stone handrails supported by stone columns. All this featured decorations hewn in stone, sober but still fanciful. The President resided in a large impressive flat provided by the office, stretching over the first and second floors, from where he was able to directly reach his office rooms. The head clerk had official lodgings on the ground floor and in the basement there were 13 small flats for civil servants.

Imperial Patent Office: entrance hall

After only 28 months, on 8 September 1905, the office moved from Luisenstraße to Gitschiner Straße, under the new President Dr Carl Hauß (1902-1912). The newspaper, Berliner Tageblatt, reported five days before the planned move: "This will be one of the biggest moves ever in Berlin. As many as 100 removal vans have been rented to master the move within twelve working days; the costs will amount to roughly 50,000 marks." The new building itself cost 7.75 million marks and the new furniture was 200,000 marks. To understand the value of one mark at that time, here is an example from the year 1905: the price for five litres of milk was one mark.

President Dr Carl Hauß

(1902-1912)

Some of the civil servants visited the offices beforehand, according to Berliner Tageblatt, in order to keep informed about the move. It is conceivable that they wanted to make sure whether, that time, there was enough space or whether they would soon have to move again. President Dr Carl Hauß was convinced that the building would be an incentive for his civil servants to set about the extra work zealously and euphorically. It is not surprising that he bestowed such high praise on some "servants of the empire" for their industriousness since they had kept on working during the move inside the removal van.

The office building was one of the biggest buildings in Berlin at the turn of the century and, today, it is listed as a historic monument. It houses, among other things, the Technical Information Centre of the German Patent and Trade Mark Office.

Tense atmosphere among civil servants

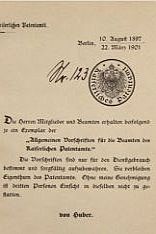

Order by President von Huber

The "General Rules for Civil Servants of the Imperial Patent Office", confirmed by President Otto von Huber in 1901, provide an interesting insight into the daily working routine.

To make sure that discipline was kept in the office building, the civil servants had to observe the absolutely effective rule that it was "permitted to stay in other office rooms than those allocated ... only due to official Business". Possibly, some of the technical assistants, in particular, had doubts about the meaningfulness of the rule. A contemporary witness described a momentous incident: technical assistants met a few times in the office of a colleague to "discuss personal matters". All of them were found "guilty of the joint offence of misuse of the working time and the office room". The wrongful act was examined and "the majority of the sinners, apart from some exceptions, got off lightly but some of the colleagues voluntarily turned their backs on the office and some of those who left were not the worst."

The compulsory time of attendance depended on the rank of the staff members. "The gentlemen holding a full-time post" were requested to be present at the office building from eleven to two o'clock "to facilitate oral communication". Should they leave it during that time, they had to leave a message on their desks indicating the duration of absence. However, the technical assistants had to be present from nine to three o'clock. If they wanted to leave the office building due to special reasons, they had to see to it themselves that "an entry is made in the registration book, which is laid out and provides information on the time of the entry, the reason and the duration of the absence." It seems that today's core hours at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office are modelled on the working hours of 116 years ago.

Then, the office had existed for over 20 years, during which period neither the technical assistants nor the lawyers had been bored: because "it was a field which was not spoiled by centuries-old case law but a field where those having a sufficiently open mind had the opportunity to break new intellectual ground". And this applied to more than 600 staff in the year 1900, to 729 staff only one year later. These included civil servants and assistant staff, among the latter 18 full-time legally qualified members, 71 full-time technically qualified members and 28 part-time technically qualified members. For years, the IP applications grew at a high level, which resulted in the setting up of a second and a third trade mark division, in 1905 and 1910, respectively. On 14 May 1908, German emperor Wilhelm II even decreed the establishment of a separate division for patent applications, which was called "Application Division XI".

The Patent Office at the international level

Examiner in the library

On 1 May 1903, Germany became party to the Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, adopted on 20 March 1883. It constitutes an international treaty, still valid today, prescribing provisions for cooperation between the international contracting parties. This allowed the German empire to show its modern and cosmopolitan side although only 26 years had passed since nation-wide uniform patent protection had been achieved. The Paris Convention contains legal principles regarding patents, trade marks, industrial designs and utility models, but also provisions against unfair competition. In this respect, the "Act on Combating Unfair Competition"(Gesetz zur Bekämpfung des unlauteren Wettbewerbs) entered into force in the German empire, on 1 July 1896.

Article 4 A(1) of the Paris Convention contains the provision on the right of priority, also called "Union priority right": "Any person who has duly filed an application for a patent, or for the registration of a utility model, or of an industrial design, or of a trademark, in one of the countries of the Union, or his successor in title, shall enjoy, for the purpose of filing in the other countries, a right of priority during a period of six months or twelve months, respectively." That means: from the filing date, the applicant is allowed to file an application for the invention also in another contracting state, within a time limit, and retains the filing date of the first application as priority date.

National treatment is another important principle, stipulated in Article 2(1) of the Paris Convention. When filing an IP application in a country other than their own country, the acts on industrial property protection of the respective country are applicable to nationals of any country of the Union.

At that time, the Patent Office also exerted a strong pull on the German society as well as on foreign countries. New ideas mean progress, suggest a fresh start, adventure, prosperity. The location where knowledge is accumulated is fascinating: from the receipt of the application documents at the Document Receiving Service, to the examination and to the stockroom filled with the intellectual creations of the past centuries. And also due to a quality of civil servants, which appears to be inconspicuous, which sometimes is questioned but which exists and has a particular value not only for the administration. What is it about? Well, the former President Carl Hauß recognised this particular quality on occasion of the visit of a delegation of the office of another country. After a guided tour of the office, the head of the delegation confidentially asked the President for an explanation. "Your examination system," he began, "can only be carried out if you are absolutely sure about the discretion of all civil servants and feel certain that they are unapproachable to external attempts to influence them. What guarantee do you have?" President Hauß smiled and answered that he was absolutely sure about the loyalty of the civil servants so that nothing to that effect could happen. Obviously astonished, the visitor bade farewell remarking: "Your system is not feasible to us."

Pictures: DPMA (unless otherwise noted)

Last updated: 10 December 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media