Content

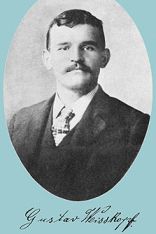

Gustave Whitehead´s 150th birthday

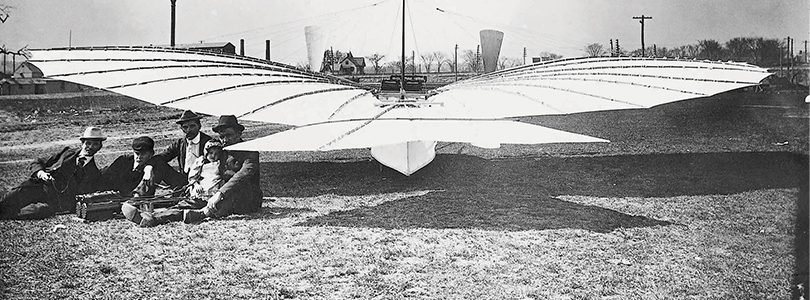

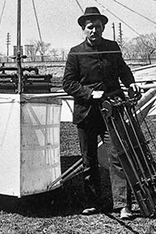

Gustav Weißkopf with his little daughter and the "Nr. 21", 1901

Wright or wrong? The Whitehead mystery of the world's first flight

To fly or to lie, that is the question: perhaps the world's first powered flight took place on 14 August 1901 in Bridgeport, Connecticut - or perhaps not. Few questions in the history of technology are as hotly debated as whether the Wright brothers were the first powered pilots when they took off in their "Flyer" from Kitty Hawk on 17 December 1903 - or Gustav Weisskopf/Gustave Whitehead more than two years earlier?

"Confused by the parties' favour and hatred, his character fluctuates in history": Schiller wrote this about Wallenstein, but it could also apply to Weißkopf. For a century, the strategy of Wright's supporters has been to discredit the Bavarian as either a windbag, a dreamer or a chronic boaster. Others see him as a visionary, an excellent engineer and a glorious pioneer.

The Weißkopf controversy is a real scientific thriller with villains and heroes, without it being entirely clear who is who. The fact is that it cannot be proven beyond all doubt that Weißkopf's powered flight of 14 August 1901 actually took place. However, it is also a fact that the Wrights asserted their claim to the fame of the first powered flight more purposefully and eloquently on the one hand, but also with questionable means on the other. And that their first flight also raises some questions...

A Bavarian in Boston

But let's start at the beginning: Gustav Albin Weißkopf was born on 1 January 1874 in Leutershausen near Ansbach. Since 1974, the Franconian community has honoured him with a ![]() museum, which was recently redesigned. Not much is known about his early years: Both his parents die when he is still a child. He was temporarily apprenticed to a bookbinder and a locksmith, then ended up on a sailing ship in Hamburg (he was probably "schanghait") and probably travelled as a sailor for several years. He is also said to have spent some time in Brazil. In any case, he can be traced back to the USA from 1894 and Americanised his name to "Gustave Whitehead".

museum, which was recently redesigned. Not much is known about his early years: Both his parents die when he is still a child. He was temporarily apprenticed to a bookbinder and a locksmith, then ended up on a sailing ship in Hamburg (he was probably "schanghait") and probably travelled as a sailor for several years. He is also said to have spent some time in Brazil. In any case, he can be traced back to the USA from 1894 and Americanised his name to "Gustave Whitehead".

In Boston, he worked as an assistant to Harvard professor William Pickering. Here he met James Means, who founded the Boston Aeronautical Society in 1895. He wanted to build gliders modelled on Otto Lilienthal. Weißkopf was hired because he claimed to know Lilienthal and even to have worked with him (which, like some other things in Weißkopf's CV, cannot be clearly proven). However, he probably translated Lilienthal's writings for the Society.

In 1897, we find him in New York, where he builds his own gliders and successfully demonstrates them to the public and the press. A few weeks later, he married and listed "aeronaut" as his profession on his marriage licence. He moved to Pittsburgh, where he is said to have made his first flight with a steam engine-powered glider as early as 1899, but it ended on the wall of a house. There are individual witness statements for this and other Weißkopf flights, but no further evidence.

"No. 21" - the first airplane in the world?

1900 he moves to Bridgeport, where he develops his aircraft no. 21, called "Condor". He designed and built both the aircraft and the engines himself. The "Condor" has two propellers powered by a 20 HP engine and a landing gear with an additional 10 HP engine for starting acceleration. This means that the No. 21 can also drive on the road when the wings are folded up.

And so in the early morning hours of August 14, 1901 (possibly?) the first engine-powered flight in history takes place - if you believe a reporter of the local weekly "Bridgeport Sunday Herald".

In order not to cause a stir, "No. 21" is rolled onto the road at midnight by Weißkopf and his two colleagues Dickie and Cellie. Then she drives under her own power to the test site, a large meadow, ![]() reports the journalist (possibly "Herald" editor-in-chief Richard Howell). There it first comes to an unmanned test flight with two sandbags as weight instead of the pilot. The engines are started, the assistants hold the aircraft with ropes. Then the No. 21 is released - and takes off: “She looked for all the world like a great white goose raising from the feeding ground in the early morning dawn”, reports the “Herald”. A timer ensures that the engines stop after a short time; the machine glides back to the ground.

reports the journalist (possibly "Herald" editor-in-chief Richard Howell). There it first comes to an unmanned test flight with two sandbags as weight instead of the pilot. The engines are started, the assistants hold the aircraft with ropes. Then the No. 21 is released - and takes off: “She looked for all the world like a great white goose raising from the feeding ground in the early morning dawn”, reports the “Herald”. A timer ensures that the engines stop after a short time; the machine glides back to the ground.

Weißkopf is enthusiastic about the test. A short time later he himself takes off with the No. 21, which thus becomes the first real aircraft in history. He flies straight ahead for a few minutes, avoids a few trees by shifting his weight and lands safely again.

Bridgeport Sunday Herald, August 18, 1901, page 5

It was an exciting moment. "We can’t hold her!" shrieked one of the rope men. "Let go then!" shouted Whitehead back. They let go and as they did so the machine darted up through the air like a bird released from a cage. Whitehead was greatly excited and his hands flew from one part of the machine to another.

The newspaper man and the two assistants stood still for a moment watching the air ship in amazement. Then they rushed down the sloping grade after the airship. She was flying now about fifty feet above the ground and made a noise very much like the "chug, chug, chug," of an elevator going down the shaft.

Whitehead had grown calmer now and seemed to be enjoying the exhilaration of the novelty. (…) He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, "I’ve got it at last." He had now soared through the air for fully half a mile and as the field ended a short distance ahead the aeronaut shut off the power and prepared to light. He appeared to be a little fearful that the machine would dip ahead or tip back when the power was shut off but there was no sign of any such move on the part of the big bird. She settled down from a height of about fifty feet in two minutes after the propellers stopped. And she lighted on the ground on her four wooden wheels so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least.

How the inventors face beamed with joy! (…) "I told you it would be a success," was all he could say for some time. He was like a man who is exhausted after passing through a severe ordeal. And this had been a severe ordeal to him. For months, yes years he had been looking forward to this time, when he would fly like a bird through the air by means that he had studied with his own brain. He was exhausted and he sat down on the green grass beside the fence and looked away where the sun’s first rays of light were shooting above the gray shrouding fog that nestled on the bosom of Long Island Sound. (…)

The most wanted photo in the history of technology

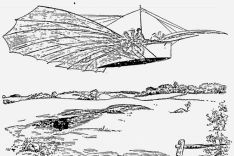

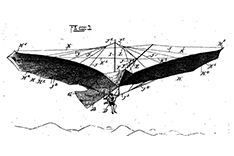

The “Herald” journalist is reported to have taken a photograph, but it's lost. A lithograph, however, has survived, which was printed with the report on August 18, 1901. The fact that there is no photo of the flight is an important point of the Weißkopf opponents. At that time, however, it was customary for newspapers to design lithographs from photos and to print them. This was much easier and cheaper; furthermore, around 1900 the image quality of photos was often still very poor, especially with such snapshots.

The report of the "Bridgeport Herald" was picked up by several other papers. The flight historian and pilot John Brown, who rekindled the controversy about the first powered flight through his publications some years ago, found ![]() 136 contemporary articles about Weißkopf's powered flights in the years 1901/1902.

136 contemporary articles about Weißkopf's powered flights in the years 1901/1902.

In January 1902 Weißkopf claims to have built his "No. 22", now no longer from wood and canvas, but metal and silk. Eyewitnesses report on a 40 hp self-ignition engine and a rudder (an invention that the Wright brothers later claimed for themselves). On January 17, 1902, Weißkopf made a flight about 11 km over the Long Island Sound, according to one of his letters.

No patents that support Weißkopf's claim

The problem is that Weißkopf occasionally made contradictory statements about his flights and apparatus. In contrast to the Wrights, he does not seem to have documented his experiments in detail. There are no pictures of "No. 22", so opponents of Weißkopf speculate that it never existed. It is interesting to note that Whitehead/Weißkopf did not apply for a patent for an "Aeroplane" ( ![]() US881837A) until December 1905 - but this was a glider without an engine. He also registered the same glider in Great Britain (

US881837A) until December 1905 - but this was a glider without an engine. He also registered the same glider in Great Britain ( ![]() GB190805312A), France and Austria.

GB190805312A), France and Austria.

The Wrights on the other hand - professionals in PR as well as in IP! - had already filed a patent on their flyer ( ![]() US821393A (1,22 MB), "Flying Machine") before making their first flights in Kitty Hawk. Later they submitted many more applications (e.g.

US821393A (1,22 MB), "Flying Machine") before making their first flights in Kitty Hawk. Later they submitted many more applications (e.g. ![]() US1075533A (1,22 MB),

US1075533A (1,22 MB), ![]() US1122348A).

US1122348A).

Property right management and PR do not seem to have been among Weißkopf's strengths, nor does commercial intuition. But maybe he didn't have much interest in self-marketing either, because he had the feeling that he hadn't yet reached his ambitious technical goals: "The flights are all useless because they don't last long enough," he is reported to have said. "Flying will only take on meaning if we can fly to any place at any time."

Sad ending

Whitehead became quite famous over the next few years thanks to the reports of his flights. However, he got involved in business with the wrong people, suffered financial shipwreck and in future concentrated on building engines for flying machines (possibly quite successfully, but this is also disputed in the literature). He does not appear to have made any further successful flight attempts (at least none are documented), which is an argument for Weisskopf critics to also question the flights of 1901-02.

After his engine factory went bankrupt, Weißkopf kept his family and himself afloat as a simple factory worker. He died impoverished in Bridgeport on 10 October 1927, aged just 53.

A dubious secret contract

Did he fly or not? For Weißkopf researcher John Brown it is clear: the available witness statements and reports would be sufficient evidence for a conviction in court; so why, conversely, refuse to recognise Weißkopf any longer?

The missing photo is always the main argument of Weißkopf's opponents. In contrast, there are razor-sharp photos of the Wright brothers' first flight. When the debate about the first motorised pilot flared up in the 1930s, Orville Wright argued against Weisskopf that he had made remarkably little public fuss immediately after his first flight (although the newspapers did report on it). In retrospect, this seems curious, as the Wrights did not publish photos and beat the PR drum for their first flight until five years after the hop from Kitty Hawk. For this reason, it cannot be proven with absolute certainty that these photos were actually taken in 1903 or that the Flyer actually took off under its own power.

Among the influential opponents of the Weisskopf theory are the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington and its curator Tom Crouch. However, his vehement support of the Wright brothers and ![]() rejection of Weißkopf has a flaw: when Orville Wright gave the original flyer of Kitty Hawk to the museum in 1948, it had to sign a

rejection of Weißkopf has a flaw: when Orville Wright gave the original flyer of Kitty Hawk to the museum in 1948, it had to sign a ![]() secret contract . In it, it had to commit itself never to question the fact that it were the Wrights who made the first powered flight in history.

secret contract . In it, it had to commit itself never to question the fact that it were the Wrights who made the first powered flight in history.

Blurred evidence?

On the photograph of an exhibition of the "Aero Club of America" in New York in 1906, John Brown claims to have discovered a picture that ![]() shows Weißkopf's maiden flight and served as a model for the lithograph. However, this image is so small and blurred that its interpretation seems quite daring. But Brown's theses made sure that the discussion was rekindled. The most traditional US aviation magazine "Jane's All the Worlds Aircraft" recognised Gustav Weißkopf's claim to the first powered flight in 2013, but later relativized this decision.

shows Weißkopf's maiden flight and served as a model for the lithograph. However, this image is so small and blurred that its interpretation seems quite daring. But Brown's theses made sure that the discussion was rekindled. The most traditional US aviation magazine "Jane's All the Worlds Aircraft" recognised Gustav Weißkopf's claim to the first powered flight in 2013, but later relativized this decision.

Why didn't Weißkopf keep trying?

Weißkopf's opponents often cite the fact that after the reasonably well-documented successful attempts with the "No. 21" and the longer flights with the "No. 22" in the following year, which cannot be documented, he apparently made no further attempts with motorised aircraft. In fact, Weißkopf seems to have continued to build engines, but otherwise only gliders.

There are a number of good reasons why Weißkopf may have decided to discontinue his motorised flight experiments: for example, his financial problems, his commercial ineptitude, the enormous risks, consideration for his family (he now had three small children), work on his patent applications, distraction by other tasks such as setting up his engine factory and exhaustion due to years of double workload. Or simply frustration: his attempts at flying may have made him realise that he could not achieve his ideal of a piloted, bird-like long-distance flight with his means. Bad luck probably also played a part: "No. 22" was badly damaged by winter weather as it stood unprotected in the backyard, according to reports; a prototype engine is said to have been accidentally sunk by boat in Long Island Sound by a backer during testing.

Health problems may also have played a role. What is certain is that he was seriously injured in several accidents at work in his workshop: he lost an eye; a severe chest injury may have favoured the heart attack to which he later succumbed.

Time to celebrate the true pioneer

Regardless of who really was the first motorised pilot, the Wrights' significance for the development of aviation was far greater, as they dominated the early years of flight from around 1908 onwards as shrewd businessmen, fierce enforcers of their patents and PR professionals.

All that is certain for the time being is that Gustav Weißkopf was one of the most important pioneers of the aviation age. Others are also credited with more or less successful experiments with motorised gliders, such as Clément Ader (France 1890), Augustus M. Herring (USA 1898) Wilhelm Kress (Vienna 1901), Richard Pearse (New Zealand 1903), Karl Jatho (Hanover 1903) and Samuel Langley (USA 1903).

Compared to these other pioneers, the evidence for a successful motor flight by Weißkopf is much better. But unfortunately not good enough to knock the Wrights off their pedestal in the public perception, it seems. Perhaps the 150th birthday of the courageous Franconian will finally be the occasion to give him the honour he (most probably) deserves: that he was the world's first motorised pilot!

Text: Dr. Jan Björn Potthast; Pictures: Valerian Gribayedoff/Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, DEPATISnet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, Bridgeport Sunday Herald - Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons, John T. Daniels - Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, Gustav Weisskopf Museum Pioniere der Lüfte, via wikimedia Commons

Last updated: 10 December 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media