Content

275th birthday of Caroline Herschel

Caroline Herschel, 1829

A woman reaches for the stars

Caroline Herschel, who was born in Hanover on 16 March 1750, was a pioneer in more ways than one. She was one of the first women to earn the honour and recognition of the scientific community in a natural science. And she was the first female scientist to be paid for it - the world's first professional female astronomer!

If it had been up to her mother, nobody would know her name today. Caroline Lucretia Herschel was the second youngest of Isaak and Anne Ilse Herschel's six surviving children and the youngest daughter. Her older brothers received a solid musical education from their father, who worked as a military musician. Caroline was also allowed to practice the violin and even learn reading and writing at the garrison school (but not arithmetic), which was still completely unusual for girls at the time.

Her mother saw Caroline primarily as a domestic help, especially after her older sister marries. According to her mother, she should be and remain ‘a rough lump, but a useful one’. Caroline had to cook and serve the family. Her father would have liked to send her to secondary school, but her mother insisted that she should be apprenticed to a seamstress. She had to sew, knit, hem and embroider stockings, bonnets and blankets for the family.

‘Abigail’ forever?

‘I couldn't bear the thought of becoming an Abigail or a housemaid,’ Caroline Herschel later recalled. Her father secretly continued her musical education and explained the starry night sky to her and her brothers. This awakened her and her twelve-year-old brother Wilhelm's enthusiasm for astronomy.

As a child, she fell ill with typhoid fever. This impaired her growth; she was to remain around 1.40 metres small. When she was 17 years old, her father died. Her brothers were now all working in England (which at the time was in personal union with Hanover; the Elector was also King of Great Britain). She was indispensable to her mother as a domestic help. Her fate as a an "Abigail" seemed sealed.

Help from England

But she was „rescued“ by her brother Wilhelm. He had made a name for himself as a composer and orchestra leader in Bath, England, and brought Caroline to live with him in 1772. Of course, her mother only let her go when Wilhelm promised her enough money to hire a housemaid to replace Caroline.

Caroline now took care of the household for Wilhelm - but not only that: she now studied English and maths with her brother with great enthusiasm. She also trained as a singer and eventually had considerable success, for example as a soloist in Handel's ‘Messiah’ under her brother's direction.

But in addition to music, they both had a shared hobby that increasingly became both a vocation and a profession: astronomy. From the ‘apprentice’ who literally has to feed her brother because he works almost non-stop, Caroline grew over the years to become Wilhelm's congenial partner. The two became a team that wrote scientific history.

A discovery changes the universe

They built telescopes, initially with a magnification of 2,000 to 6,000 times, which was sensational at the time and allowed a good view of the moon's craters, for example. The telescopes soon became ever larger and more elaborate, sometimes at the risk of life and limb, and some were even sold. They spend their nights observing the sky: Wilhelm observed, she noted and analysed the data, drew up systematics and observation plans.

In 1777, they moved into a new house in Bath (19 King Street), which can be visited today as the Herschel Museum. Something happened there that would change both their lives and astronomy forever: On 13 March 1781, Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel discovered a new planet - Uranus.

Thanks to this scientific sensation, Wilhelm became famous practically overnight. From one day to the next, the known solar system grew eightfold! King George III offered Herschel the position of royal court astronomer with an annual salary of 200 pounds. At last he could turn his passion into a profession.

A job offer of historic dimensions

Caroline also decided not to continue her career as a musician and to devote herself entirely to science together with Wilhelm. And indeed, from 1787, she also received a fixed salary of £50 from the court as William's recognised scientific assistant. This made her the first professional astronomer in the world and probably the first woman ever to be paid for a scientific activity.

This meant a great deal to Caroline. It is ‘the first money I have had for myself in my whole life and could use as I pleased. It removed a very uneasy feeling from my soul.’

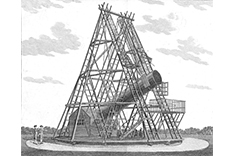

In 1786, the couple moved to Slough, where they had a 13-metre-long telescope with a diameter of 1.5 metres built - an attraction that drew many visitors (including Joseph Haydn), who sometimes even spoke of a ‘wonder of the world’. Caroline now also conducts research directly at the telescope (especially when her brother is away).

The comet hunter

When Wilhelm married in 1788, Caroline gave up ‘my post as housekeeper’ and moved into a rented flat. She initially met her sister-in-law with mistrust, but when her nephew John was born in 1792, with whom she would have a close relationship for the rest of her life, the relationship improved (John later also became a famous astronomer and polymath).

The siblings continued to be a successful scientific team. Caroline was now increasingly able to conduct her own research. On 1 August 1786, Caroline discovered her first comet (35P/Herschel-Rigollet). As far as is known, she was the first woman ever to achieve this. Her supporter, Sir Joseph Banks, and the Royal Society, promoted the communication of the discovery - her first scientific publication.

Caroline discovered a total of 8 comets, as well as hundreds of nebulae and star clusters. In 1797, she presented the Royal Society with an index and additions to John Flamsteed's star catalogue, including a list of 561 stars that had previously been missing.

Home after half a century

When Wilhelm died in 1822, Caroline decided to leave England after 50 years and return to Hanover. She spend her long retirement with her brother Dietrich's family. The little old lady had long since become a celebrity in scientific circles and received several international scientific honours, such as the gold medal and honorary membership of the Royal Astronomical Society (again as the first woman). Famous scientists such as Carl Friedrich Gauss and Alexander von Humboldt visited her.

Caroline Herschel died at the age of 97 on 9 January 1848 in Hanover. Since 2022, the Royal Astronomical Society and the Astronomische Gesellschaft have jointly awarded the Caroline Herschel Medal, which alternately honours British and German female astronomers.

Text: Dr. Jan Björn Potthast, Pictures: Melchior Gommar Tieleman (Foto unbekannt; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons), Lemuel Francis Abbott (Nattional Portrait Gallery, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons), Paul Fouch (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons), Herschel Museum of Astronomy (Foto: Mike Peel, CC by SA 4.0), Library of Congress 2004669299 Popular Graphic Arts Publiic domain via Wikimedia Commons, Georg Müller (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Last updated: 29 January 2026

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media