Content

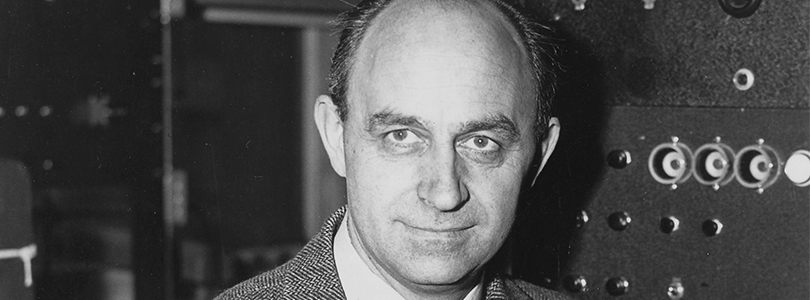

Enrico Fermi

The man who knew everything

Enrico Fermi was one of the most important physicists of the 20th century. He is often called the "father of the nuclear age" because he built the first nuclear reactor and helped develop the atomic bomb. But Fermi's work goes far beyond that.

Fermi, who was born in Rome on 29 September 1901, showed his superior talent early on. He received his doctorate at the age of 20 and became Italy's youngest physics professor at 26. In between, he studied with Max Born in Göttingen as a scholarship holder. Early on, he was intensively involved with Einstein's theory of relativity and traced the hidden power of atomic nuclei. In 1923, he wrote that it would probably not be possible to release this energy in the near future, "because the first effect would be an explosion so terrible that it would tear the physicist who tried it to pieces". He himself was to unleash this energy two decades later.

In Rome, he achieved groundbreaking research in bombarding chemical elements with neutrons. He discovered that slowed neutrons are more reactive than fast ones. In 1938, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "for his work with artificial radioactivity produced by neutrons, and for nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons".

Escape from the fascists

He did not return home from the award ceremony in Stockholm: the fascist regime in Italy threatened his Jewish wife Laura. Fermi and his family emigrated to the USA, where the elite universities welcomed the brilliant researcher with open arms.

Like Fermi, almost all the important atomic physicists from Hitler's and Mussolini's spheres of power had fled to America, such as Leo Szilard. In 1934, Szilard had applied for patents in which, among other things, he sketched a nuclear chain reaction when a critical mass was exceeded (e.g. ![]() GB440023A (1,31 MB)). Szilard thus practically owned a patent on the functional principle of nuclear energy - and nuclear weapons. However, the far-sighted physicist did not want his ideas to be published. Therefore, the exile left his patents to the British, later to the American government.

GB440023A (1,31 MB)). Szilard thus practically owned a patent on the functional principle of nuclear energy - and nuclear weapons. However, the far-sighted physicist did not want his ideas to be published. Therefore, the exile left his patents to the British, later to the American government.

Shock news from Berlin

When news of Otto Hahn's and Fritz Straßmann's Berlin uranium experiment reached the USA at the beginning of 1939, which Lise Meitner correctly interpreted from her exile in Sweden as the first nuclear fission in history, physics finally became political.

Fermi, Szilard and other exiles immediately recognised the threat posed by a Nazi Germany with nuclear weapons. Szilard drafted a famous letter in which Albert Einstein drew the attention of the US President to this danger in August 1939. This set in motion the USA's now steadily intensifying preoccupation with nuclear energy. From the end of 1941, atomic research was bundled and finally combined in the "Manhattan Project" under the direction of Robert Oppenheimer, which led to the Hiroshima bomb.

The reactor under the grandstand

"Neutron Pope" Fermi was a key figure in this development: he prepared the world's first controlled chain reaction. On the morning of 2 December 1942, a few dozen scientists and a handful of guests gathered under the bleachers of the disused football stadium "Stagg Field" in Chicago. There, where students had once played squash, the "Chicago Pile 1", or CP-1 for short, had been created under Fermi's direction. In this pile, a self-sustaining fission chain reaction was to be set in motion and controlled.

The original reactor - "a crude pile of black bricks and wooden timbers", as Fermi described it - was a 7.6 metre high, almost spherical pile of blocks. It consisted of 5.4 tonnes of uranium metal, 45 tonnes of uranium oxide and 360 tonnes of graphite. Layers of graphite and uranium alternated, with the graphite completely encasing the uranium. Fermi and colleagues assumed that the neutrons released by the natural decay of uranium would form unstable isotopes with other uranium atoms, which in turn would decay into two different elements and release a large amount of energy in addition to more neutrons through this nuclear fission. Cadmium plates that could be lowered into slots in the reactor core were used to control the reaction. By measuring the neutron flux, the intensity of the reaction could be observed.

The "pile" marks the beginning of the nuclear age

There was no radiation protection and no cooling system. The experimental reactor had a power output of only 0.5 watts; the resulting heat was kept within limits. This was because Fermi's CP-1, the world's first nuclear reactor, had not been developed to generate energy. The actual aim of the work was to produce weapons-grade plutonium from uranium-238 for the "Manhattan Project".

The experiment on that 2nd December was delayed into the afternoon. Leona Woods, the only female researcher on the "Chicago Pile-1" team, took over the countdown. The first critical chain reaction began at 3:22 pm and was completed after 28 minutes. The start of the atomic age was celebrated with a single bottle of Chianti and paper cups, then everybody went back to work.

Secret patents

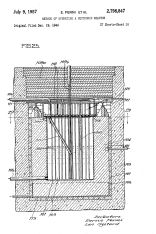

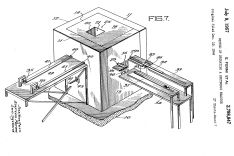

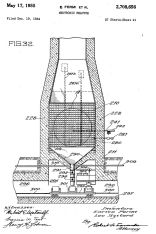

Fermi processed the findings from the experiments with CP-1 and its successors into several patent applications, some of which he filed jointly with Leo Szilard: "Test exponential pile" ( ![]() US2780595A (1,6 MB), filed May 1944, not published until 1957), "Neutronic reactor" (

US2780595A (1,6 MB), filed May 1944, not published until 1957), "Neutronic reactor" ( ![]() US2798656A (5,18 MB),filed December 1944, published 1955) or "Method of operating a neutronic reactor" (

US2798656A (5,18 MB),filed December 1944, published 1955) or "Method of operating a neutronic reactor" ( ![]() US2798847A (5,97 MB), filed December 1944, published 1955). All applications were kept secret by the US government.

US2798847A (5,97 MB), filed December 1944, published 1955). All applications were kept secret by the US government.

After experiments with further trial reactors, Fermi moved to Los Alamos and, as a leading member of the "Manhattan Project", made a decisive contribution to the USA being able to detonate an atomic bomb called "Trinity" for the first time on 16 July 1945. A few weeks later, the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing unprecedented devastation.

The last man who knew everything?

After the end of the Second World War, Fermi returned to Chicago, where he accepted a professorship and became co-founder of the "Institute for Nuclear Studies", which would later bear his name. The Nobel Prize was followed by many other awards and honours. But he did not have much time: like many other nuclear physicists of the early days, he succumbed to cancer and died on 28 November 1954.

Prizes, institutes, formulae, paradoxes, elements and much more were named after Fermi, who is said to have been not only one of the most brilliant physicists, but also an immensely popular, cheerful person. His comprehensive knowledge of all areas of physics or even his ability to give rapid quantitative assessments without comprehensive data ("Fermi problems") contributed to the fact that he was believed to be capable of practically anything: "The Last Man Who Knew Everything" is therefore the title of a recent biography.

Text: Dr. Jan Björn Potthast; Pictures: NARA / via Wikimedia Commons, DEPATISnet, Energy.gov / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, Jack W. Aeby / Public domain via Wikimedia commons

Last updated: 10 December 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media