Content

A poor student becomes a pioneer of television

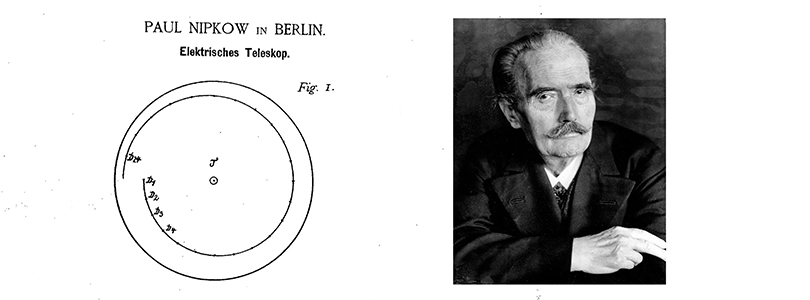

Detail from DE30105 and photo of Paul Nipkow (1935)

The ‘Nipkow disc’

For more than half a century, television was the most important medium for mankind. Today, as its importance is declining in the face of the digital revolution, it is worth taking a look at its roots. It began with the idea of a lonesome student.

Paul Nipkow, who already stood out as a schoolboy thanks to his technical talent, was born on 22 August 1860 as the son of a baker in Lauenburg in Pomerania (today: Lębork, Poland). The installation of the first telephone in the post office in Neustadt (West Prussia), where Nipkow attended grammar school, was a decisive experience. He borrowed this telephone from a friend who was an apprentice at the post office to examine it. In just one night, he is said to have managed to analyse the device in such a way that he was able to reproduce it. The post office received his phone back on time the next morning.

After leaving school, Nipkow moved to Berlin in 1882, where he began studying natural sciences at the Humboldt (then Friedrich Wilhelm) University. He also attended lectures at the Technical University in Charlottenburg. Adolf Slaby and Hermann Helmholtz were among his lecturers.

Christmas flash of inspiration in the student flat

Paul Nipkow as a young student

Nipkow eked out an existence as a very poor student and is said to have earned his living by playing the piano in pubs in the evenings. At Christmas Eve 1883, he didn't have enough money to travel home to his family and sat alone in his little room at Philippstraße 13a, courtyard left, 3rd floor. He probably thought how nice it would be to at least be able to see his family somehow if he couldn't be with them. And then he had the flash of inspiration that would immortalise his name.

On that Christmas night, he designed a device that was able to visualise an object at any other location. To do this, he sketched a scanning disc with holes arranged in a spiral, which was rotated quickly and evenly around its axis by a clockwork mechanism. The scanning disc rotated over an image surface and scanned it in lines. The different brightness values of the individual pixels were converted into electrical signals in conjunction with a light-sensitive selenium cell and transmitted to a receiving station. In the receiving station, a second disc running synchronously with the scanning disc ensured the correct reconstruction of the image. The basic principle of television!

Far ahead of its time

Nipkow did not have the money for a patent application. But his girlfriend Sophia Colonius stepped in and paid the fee for him. With retroactive effect from 6 January 1884, Paul Nipkow was granted patent ![]() DE30105 on 15 January 1885 under the name „Elektrisches Teleskop“ (‚Electric telescope’).

DE30105 on 15 January 1885 under the name „Elektrisches Teleskop“ (‚Electric telescope’).

Unfortunately, he did not have the money to pursue or exploit his invention technically and commercially. Moreover, his idea was so far ahead of the state of the art at the time that not much happened in this field in the following decades. It is assumed that Nipkow never attempted to realise or test his ‘electric telescope’ in practice. According to experts, it probably could not have worked at all in 1884 (e.g. selenium resistor too slow to convert pixel brightness; light relay would have required more current than could be generated with the selenium resistor; self-induction of the coil would not have allowed the necessary rapid current changes; problem of synchronising the two disc drives not solved).

Whimsical designs for flying machines

Nipkow therefore did not get much from his patent, but all the more from his financial backer: Nipkow and Colonius married in 1885, shortly after he had abandoned his studies - again for financial reasons. The couple had six children. Nipkow found work as an engineer for railway signalling systems at the company Zimmermann & Buchloh in Borsigwalde near Berlin.

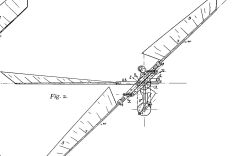

In his spare time, he occasionally devoted himself to other inventions. For example, he designed flying machines, modelled on insect flight. In 1897, he was granted a patent for a „Rad mit beweglichen Schaufeln für Luft- und Wasserfahrzeuge“ ( ![]() DE 112506,‘wheel with movable blades for aircraft and watercraft’); one year later, he was granted an additional patent for an „Insektenflugzeug“ (‘insect aeroplane’), a type of helicopter with two side propellers (

DE 112506,‘wheel with movable blades for aircraft and watercraft’); one year later, he was granted an additional patent for an „Insektenflugzeug“ (‘insect aeroplane’), a type of helicopter with two side propellers ( ![]() DE 116287). Neither invention could be realised at the time due to the lack of an engine with a sufficiently low power-to-weight ratio.

DE 116287). Neither invention could be realised at the time due to the lack of an engine with a sufficiently low power-to-weight ratio.

Re-discovered as a pioneer after decades

It took until the 1920s before electronic image transmission was decisively advanced. Then many great pioneers of television technology such as Max Dieckmann, John Logie Baird and Kenjiro Takayanagi took on to Nipkow's ideas.

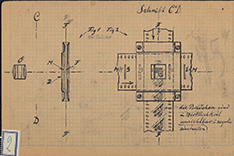

The first attempts at television transmissions all worked with optical-mechanical image scanning, most of them with a Nipkow disc. This also encouraged the now greying inventor to return to this topic and apply for several more patents. Among other things, he found solutions for the synchronisation of image transmission ( ![]() DE498415A,

DE498415A, ![]() DE577553) and a new ‘Rotating image decomposing or composing arrangement for television purposes’ (

DE577553) and a new ‘Rotating image decomposing or composing arrangement for television purposes’ ( ![]() DE685917A).

DE685917A).

The Hungarian physicist Dénes von Mihály succeeded in transmitting an image using the Nipkow method for the first time with a 2.5 km long cable. In 1928, he presented the first television pictures, measuring approximately 4 x 4 cm, to the public at the ‘5th Great German Radio Exhibition’ in Berlin.

The breakthrough of television

Further improvements in picture quality (and, from 1931, accompanying sound recordings) further advanced the development of television. In 1931, Manfred von Ardenne demonstrated the first experimental set-up for the transmission of moving images with electronic image scanning. He used the cathode ray tube developed by Ferdinand Braun (Braunʼs tube). Fully electronically, he achieved a higher quality than with the electronic-mechanical Nipkow disc, which soon became technically obsolete.

Television experienced its breakthrough in 1936 with direct broadcasts of the Olympic Games from Berlin. The picture quality was initially poor: 180 lines per picture and 25 pictures per second were transmitted, which flickered badly and were so low in contrast that the screening had to be constantly explained by a radio announcer. Nipkow is said to have been disappointed when he saw television pictures for the first time - it was not (yet) what he had in mind on that Christmas night in 1883.

Late honour for the pioneer

But with the first successes of television, the pioneer Nipkow was remembered again. In his old age, he became a celebrated personality; for example, the university dropout received an honorary doctorate from the University of Frankfurt on his 75th birthday. After 1933, the new National Socialist rulers stylised him as the ‘inventor of television’ for propaganda purposes and named the world's first regular television station after him.

From Berlin-Witzleben, the ‘Paul Nipkow’ television station, which broadcast over a distance of around 70 kilometres, reached around 500 private television sets in Berlin in 1939; there were also several public ‘television rooms’. The home receivers cost between 2,500 and 3,600 Reichsmarks at the time (for comparison: the ‘KdF-Wagen’, forerunner of the VW Beetle, was sold for 990 marks).

In his last years, Paul Nipkow received an honorary pension and after his death on 24 August 1940 a state funeral (as the first engineer ever!) - broadcast by television cameras, of course.

- See also "

Mechanisches Fernsehen" in the DPMA poster gallery (in German only)

Mechanisches Fernsehen" in the DPMA poster gallery (in German only)

Text: Dr. Jan Björn Potthast, Pictures: DEPATISnet, Getty Images/ullstein bild, Publi domain via Wikimedia Commons, DEPATISnet, Holger.Ellgaard CC BY-SA 3.0 from Wikimedia Commons, Nachlass Nipkow CC by SA 4.0 Museumsstiftung Post und Telekommunikation

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media